Planning for Accessibility

Incorporating accessibility from the beginning is almost always easier, more effective, and less expensive than making accessibility improvements as a separate project. In fact, building accessibility into your project and processes has a wealth of business benefits. If you’re looking to make the case for accessibility—to yourself, to coworkers, or to bosses and clients—you might start here:

- Findability and ease of use: In the broadest terms, accessibility can make it easier for anyone to find, access, and use a website successfully. By ensuring better usability for all, accessibility boosts a site’s effectiveness and increases its potential audience.

- Competitive edge: The wider your audience, the greater your reach and commercial appeal. When a site is more accessible than other sites in the same market, it can lead to preferential treatment from people who struggled to use competitors’ sites. If a site is translated, or has more simply written content that improves automated translation, increased accessibility can lead to a larger audience by reaching people who speak other languages.

- Lower costs: Accessible websites can cut costs in other areas of a business. On a more accessible site, more customers can complete more tasks and transactions online, rather than needing to talk to a representative one-to-one.

- Legal protection: In a few countries, an accessible site is required by law for organizations in certain sectors—and organizations with inaccessible sites can be sued for discrimination against people with disabilities.

Once you’ve made the case for incorporating accessibility into your work, the next step is to integrate an accessibility mindset into your processes. Include accessibility by default by giving accessibility proper consideration at every step in a product’s lifecycle.

Building Your Team

Web accessibility is the responsibility of everyone who has a hand in the design of a site. Design includes all of the decisions we make when we create a product—not just the pretty bits, but the decisions about how it works and who it’s for. This means everybody involved in the project is a designer of some sort.

Each specialist is responsible for a basic understanding of their work’s impact on accessibility, and on their colleagues’ work. For example, independent consultant Anne Gibson says that information architects should keep an eye on the markup:

We may or may not be responsible for writing the HTML, but if the developers we’re working with don’t produce semantic structure, then they’re not actually representing the structures that we’re building in our designs.

Leadership and support

While we should all be attentive to how accessibility impacts our specialism, it’s important to have leadership to help determine priorities and key areas where the product’s overall accessibility needs improvement. Project manager Henny Swan (user experience and design lead at the Paciello Group, and previously of the BBC) recommends that accessibility be owned by product managers. The product managers must consider how web accessibility affects what the organization does, understand the organization’s legal duties, and consider the potential business benefits.

Sometimes people find themselves stuck within a company or team that doesn’t value accessibility. But armed with knowledge and expertise about accessibility, we can still do good work as individuals, and have a positive effect on the accessibility of a site. For example, a designer can ensure all the background and foreground text colors on their site are in good contrast, making text easier to distinguish and read.

Unfortunately, without the support and understanding of our colleagues, the accessibility of a site can easily be let down in other areas. While the colors could be accessible, if another designer has decided that the body text should be set at 12 pixels, the content will still be hard to read.

When accessibility is instituted as a company-wide practice, rather than merely observed by a few people within a team, it will inevitably be more successful. When everybody understands the importance of accessibility and their role in the project, we can make great websites.

Professional development

When you’re just starting to learn about accessibility, people in your organization will need to learn new skills and undertake training to do accessibility well.

Outside experts can often provide thorough training, with course material tailor-made to your organization. Teams can also develop their accessibility skills by learning the basics through web- and book-based research, and by attending relevant conferences and other events.

Both formal training and independent practice will cost time away from other work, but in return you’ll get rapid improvements in a team’s accessibility skills. New skills might mean initially slower site development and testing while people are still getting their heads around unfamiliar tools, techniques, and ways of thinking. Don’t be disheartened! It doesn’t take long for the regular practice of new skills to become second nature.

You might also need to hire in outside expertise to assist you in particular areas of accessibility—it’s worth considering the capabilities of your team during budgeting and decide whether additional training and help are needed. Especially when just starting out, many organizations hire consultants or new employees with accessibility expertise to help with research and testing.

When you’re trying to find the right expert for your organization’s needs, avoid just bashing “accessibility expert” into a search engine and hoping for good luck. Accessibility blogs and informational websites (see the Resources section) are probably the best place to start, as you can often find individuals and organizations who are great at teaching and communicating accessibility. The people who run accessibility websites often provide consultancy services, or will have recommendations for the best people they know.

Scoping the Project

At the beginning of a project, you’ll need to make many decisions that will have an impact on accessibility efforts and approaches, including:

- What is the purpose of your product?

- Who are the target audiences for your product? What are their needs, restrictions, and technology preferences?

- What are the goals and tasks that your product enables the user to complete?

- What is the experience your product should provide for each combination of user group and user goal?

- How can accessibility be integrated during production?

- Which target platforms, browsers, operating systems and assistive technologies should you test the product on?

If you have answers to these questions—possibly recorded more formally in an accessibility policy (which we’ll look at later in this chapter)—you’ll have something to refer to when making design decisions throughout the creation and maintenance of the product.

Keep in mind that rigid initial specifications and proposals can cause problems when a project involves research and iterative design. Being flexible during the creation of a product will allow you to make decisions based on new information, respond to any issues that arise during testing, and ensure that the launched product genuinely meets people’s needs.

If you’re hiring someone outside your organization to produce your site, you need to convey the importance of accessibility to the project. Whether you’re a project manager writing requirements, a creative agency writing a brief, or a freelance consultant scoping your intent, making accessibility a requirement will ensure there’s no ambiguity. Documenting your success criteria and sharing it with other people can help everyone understand your aims, both inside and outside your organization.

Budgeting

Accessibility isn’t a line item in an estimate or a budget—it’s an underlying practice that affects every aspect of a project.

Building an accessible site doesn’t necessarily cost more money or time than an inaccessible site, but some of the costs are different: it costs money to train your team or build alternative materials like transcripts or translations. It’s wise to consider all potential costs from the beginning and factor them into the product budget so they’re not a surprise or considered an “extra cost” when they could benefit a wide audience. You wouldn’t add a line item to make a site performant, so don’t do it for accessibility either.

If you’ve got a very small budget, rather than picking and choosing particular elements that leave some users out in favor of others, consider the least expensive options that enable the widest possible audience to access your site. For example, making a carousel that can be manipulated using only the keyboard will only benefit people using keyboard navigation. On the other hand, designing a simpler interface without a carousel will benefit everyone using the site.

Ultimately, the cost of accessibility depends on the size of the project, team, and whether you’re retrofitting an existing product or creating a new product. The more projects you work on, the better you’ll be able to estimate the impact and costs of accessibility.

Research

Research can help us gain a better understanding of the people who will be using the site. It gives us a much stronger foundation on which to make informed decisions—about accessibility, but also about every other aspect of a site’s design. As Erika Hall explains in Just Enough Research (https://a4e.link/03/01/):

Discovering how and why people behave as they do and what opportunities that presents for your business or organization will open the way to more innovative and appropriate design solutions than asking how they feel or merely tweaking your current design based on analytics.

Research isn’t just asking people what they like. If you ask people for their favorite color, and Suzy likes white but Aneel likes blue, that’s not going to help you design your website. Instead, research helps uncover people’s motivations and habits and how those might translate to their use of our sites.

Researching accessibility forces you to delve into the full range of your audiences’ needs—including differing impairments and environments—which will significantly enrich your plan for an accessible product.

Researching with real users

Online testing can be a good option for small teams with tight budgets. Additionally, in A Web for Everyone, Sarah Horton and Whitney Quesenbery observe that “including people with disabilities in user experience design is even easier if you’re doing your research or testing online.” This makes a lot of sense: it’s easier to find a wider range of people if your search can be global.

If you have the time and budget, face-to-face research has a lot more benefits. Seeing real people use your product lets you understand their environment, context, needs, and behaviors. You can see exactly how they interact with their hardware and software, and you won’t need to rely on people accurately reporting their own behavior.

For example, Emily may type a message on her mobile device using one hand, tapping letters out with her thumb. Annie types a message by holding the device in her left hand and tapping the letters out with her right index finger. Jessica dictates all her messages using voice recognition. All three of them probably think the way they use their mobile device is “normal” and not worth mentioning. But interaction designers will notice that the way they’re holding the device effects the area of the screen they can comfortably reach. People in different roles in our organizations will be better equipped to notice details relevant to their own work.

This is why it’s also valuable to have a wide range of roles involved in research. Just as with accessibility, research isn’t the sole responsibility of one person or one role. Everyone should be involved in research from beginning to end.

Recruiting people with disabilities

Recruiting people for research is hard work. Recruiting people with disabilities is even harder.

We’re often told to maximize the efficiency of our research by talking to people who fit our target audience. This is good practice, but we must ensure we avoid the “we don’t have any users with disabilities” pitfall. That’s a dark path that risks ending in disability discrimination lawsuits.

To make it simple: when you’re researching your target audience, always include people with disabilities and impairments. They’re likely to have the same motivations and habits as people without disabilities, but their needs will bring potential usability and accessibility issues to the fore much more quickly.

It can be difficult to research a broad enough group of people, and you won’t be able to learn about every impairment or combinations of impairments. Some impairments may not affect how someone uses your site. However, you can only understand how to make your site accessible to your target audience if you record the requirements of people with specialist needs.

In Just Ask: Integrating Accessibility Throughout Design, Shawn Henry reminds us to look at people with disabilities as individuals, rather than grouping them together (https://a4e.link/03/02/):

Be careful not to assume that feedback from one person with a disability applies to all people with disabilities. A person with a disability doesn’t necessarily know how other people with the same disability interact with products, nor know enough about other disabilities to provide valid guidance on other accessibility issues. Just as you would not make design decisions based on feedback from just one user, don’t make accessibility decisions based only on the recommendations of one person with a disability. What works for one person might not work for everyone with that disability or for people with other disabilities.

An important part of research with people using assistive technologies is to separate user requirements (user analysis) from technology needs (workflow analysis.) Léonie Watson, communications director and principal engineer at The Paciello Group, says that designers often conflate a particular assistive technology with a particular disability—for example, assuming that everyone using a screen reader is blind. The technology is a key part of the research, but it isn’t the same as the requirements of the individual.

Interacting with participants

In Just Ask, Henry has great advice on how to provide for, and interact with, people with disabilities in your research and testing: treat people with disabilities in the same way you’d treat anybody else.

Don’t make assumptions about what people want or need. Stick to information relevant to the participant’s interaction with your site. And for crying out loud, get to know them before you ask any personal questions. You might be curious, but it really is rude to ask, “Have you always been like that?” Once you’ve welcomed your participant and introduced the research you’re doing, “How long have you been using a screen reader?” might be a relevant question to ask. And it may get you some further contextual information if the participant is comfortable talking to you.

Learning from your research

The work doesn’t stop once you’ve done all this research. Next you have to work out how to make it useful. You need to gather all your data together and look for meaningful patterns in your observations. The goals, priorities, and motivations of people with impairments are likely to be similar to anybody else, but their barriers and tools may vary. Those barriers and tools will in turn affect the actions they take to meet their goal.

Watson emphasizes that it’s important to gather quantitative data during research and requirements gathering, so you truly understand how many people may benefit from the improvements:

It’s often the case within the disabled community that there are a few vocal people, with very decided opinions about how something should be done for their particular group. Sometimes those opinions are robust, other times they’re not—and all too often they’re to the exclusion of people with other kinds of disability.

Research is cumulative. From project to project, you’ll learn more, and be more generally informed. That doesn’t mean you’ll need to do less research on each new project—every project comes with its own unique context. But it does mean that every time you start the research on a new project, you’ll be aware of more effective research methods and what’s worked for you before.

Production and Development

Whether you’re building a system from scratch, or using existing frameworks and libraries, the technologies you use will have a huge impact on the accessibility of a product.

Being wary of the potential accessibility benefits and pitfalls of each component will help you assess its suitability for your project—and should be the responsibility of the developer to research and understand. Using frameworks or components that have a focus on accessibility, and are grounded in research and testing, can save you time and resources in the long run.

As an easy example, you may decide that Adobe Flash is not a suitable component for your system because fewer browsers come with the required plugin, particularly on mobile devices. Flash also has difficulty communicating with the accessibility layer on operating systems that provides access to assistive technologies.

And since accessibility begins with accessible content, the content management system (CMS) you choose is incredibly important. A good CMS should enable the content creator to produce content in a way that’s accessible to both the creator and the consumer.

Testing on devices

It’s worth noting that obtaining assistive technologies will make up some of your setup costs. Buying and testing with these assistive technologies throughout the development process will help developers, designers, and others understand how people interact with their work.

Many assistive technologies are inexpensive or free and make for easy initial testing. You may need to budget funds to buy other devices that don’t fall into the assistive technology category, if you don’t already use a device lab or test across multiple platforms. We’ll discuss testing more in Chapter 6.

Maintenance

We all know about those dangerous little, last-minute fixes when you’re pushing a site live. Maybe your marketing team has come up with a great concept for a landing page a week before launch: it’s rich with images and video and parallax scrolling! It tells a beautiful story of your organization, and the designer has created a working prototype that’s just stunning. You’re all so caught up in the whirlwind of the bewitching design that you forget to make the HTML accessible, but no one on the team uses assistive technology so nobody notices, and you launch it anyway.

You need to watch out for these gotchas, because you may not realize that you’ve done something to compromise accessibility until later down the line. Always test after launching or updating to ensure that last-minute launch details don’t undermine accessibility.

Again, having an accessibility policy will help you maintain high standards and prevent you from compromising on the basics, so let’s explore exactly what an accessibility policy is and how to make one.

Accessibility policies

Good accessibility policies are informed by extensive research into the needs of your target audience, and will help:

- ensure everyone in your organization understands the importance of accessibility,

- standardize the way your organization approaches accessibility, and

- prioritize user groups when handling competing needs.

The term “policy” is slightly misleading corporate-speak: an accessibility policy can be anything from a formal document that shows compliance, to a set of standards, to a casual statement that outlines your organization’s approach and intentions toward the accessibility of your site.

Guidelines in your accessibility policy should be:

- clear and simply written, so anyone in your organization can refer to your policy and understand the implications and their role;

- hierarchical, so needs are prioritized as primary, secondary, etc.; and

- testable, so you can easily determine whether your site is sufficiently accessible.

The testable criteria in your accessibility policy could be based on the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 criteria, or criteria from the standards local to your country.

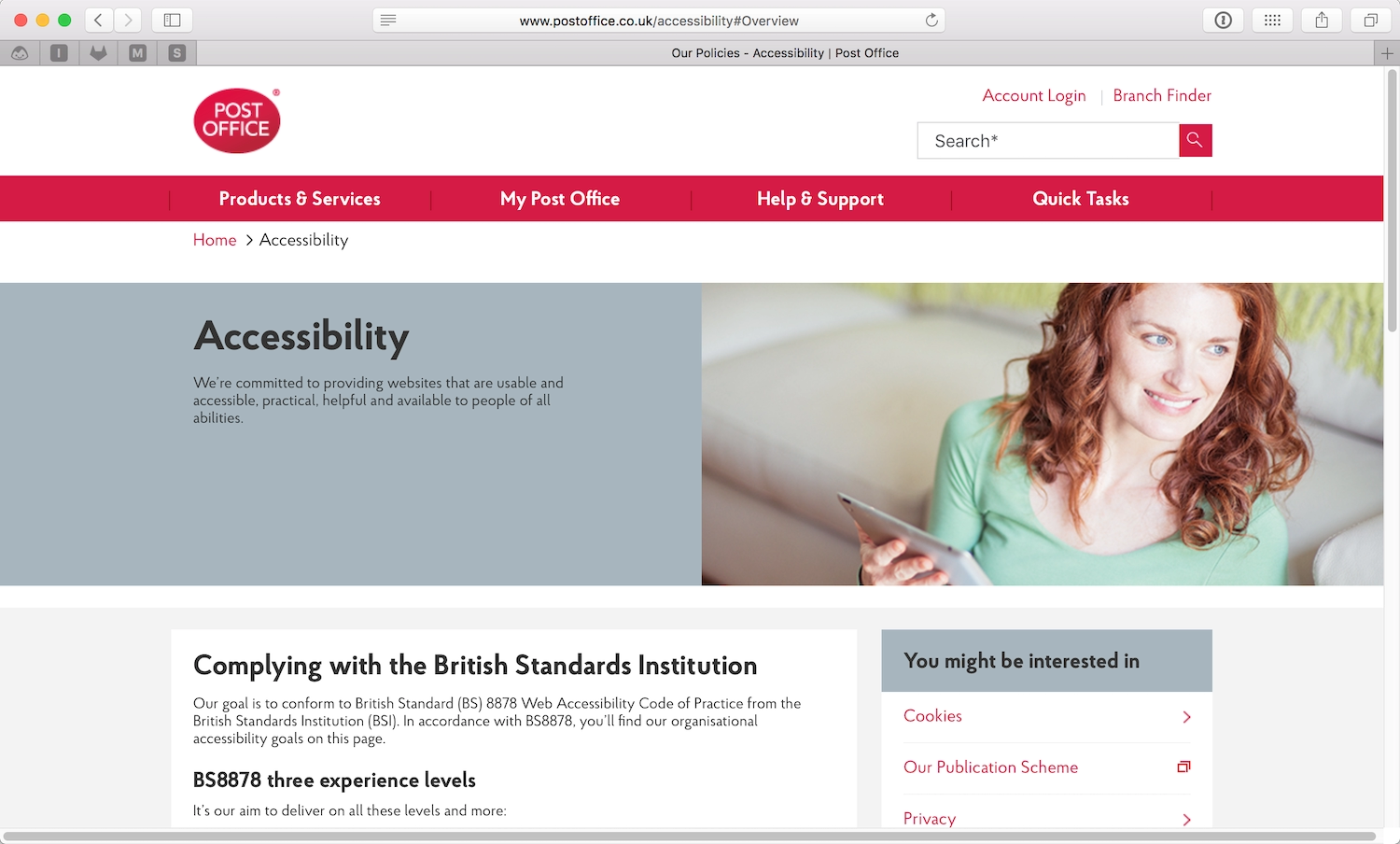

You can see a great example of an accessibility policy on the UK’s Post Office website (https://a4e.link/03/03/). The Post Office’s accessibility policy moves from general to more specific aims (Fig 3.1), covering:

- goals for the website experience,

- goals for site’s accessibility,

- the individual responsible for the policy and its implementation, and

- the accessibility of their non-digital products and services.

Accessibility policies, much like style guides, don’t always have to be made public—their primary value is as internal documents. That said, posting them publicly shows your commitment to accessibility and lets visitors know what they can expect from your site or agency.

Justifying Your Accessibility Decisions

At each stage of your process, you’ll have to make decisions about accessibility. Building your team’s accessibility skills, grounding your work in user research, and maintaining an accessibility policy that outlines your approach will not only help you make strategic decisions, but justify them as well—to yourself, your clients, and your stakeholders.

Now let’s look at how we can make our sites more accessible today—starting with content and design.